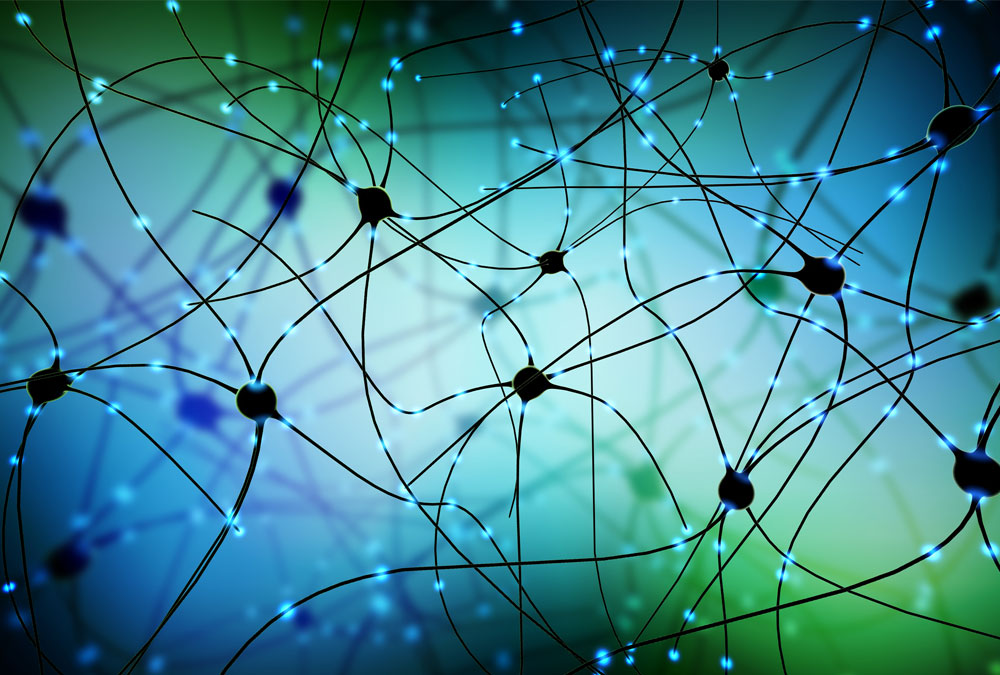

Understanding the brain in a state of addiction can add another layer to an already complicated undertaking. It is widely known that using chemical substances alters the function of the brain—and, by extension, the body—but why it does so is an important part of the puzzle of understanding addiction.

The Brain and Addiction

To understand how the brain and addiction are related to one another, it helps to first establish a point of reference. This can be done by comparing a healthy brain that is not affected by long-term substance use with a brain that has experienced the effects of addiction. Neurological images reveal noticeable differences in brain activity when compared side by side. In other words, there is visual and physical evidence that substance use limits brain activity.

When comparing the two images, the most significant difference is diminished activity in the frontal cortex of the brain exposed to SUD. The frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex, or frontal cortex, sits right behind the forehead. It is a vital component in cognitive functions like decision-making, judgment, and reasoning. It also serves as the source of the conscience. This part of the brain is also responsible for memory, abstract thought, social appropriateness, voluntary movement and motor skills, and creativity.

Other roles of the frontal cortex include the following:

- Future planning, self-management, and decision-making

- Speech and language production and forming thoughts into words

- Some motor skills like walking and running

- Some motor skills like walking and running

- The ability to make comparisons and distinguish one thing from another via categorization and classification

- Long-term memory

- Empathy and sympathy

- Personality formation via an interwoven and intricate interplay of traits like impulse control, memory, reaction, and many other key components that make up an individual’s personality

- Attention management

- Reward-seeking and motivated behaviors, as the frontal lobe contains many dopamine-sensitive neurons.

How the brain interacts with substance use is only part of the story. Further explanation of how the brain and substance use interrelate requires learning about the subject from a different perspective. In fact, another important component of understanding addiction is removing the stigma attached to the disease.

When addiction is seen in a different light, it broadens our ability to see more of the picture. By viewing addiction as substance use disorder, or SUD, we can understand the scientific concepts behind the brain and addiction.

SUD and Chronic Diseases

Defining SUD by comparing it to other chronic disorders helps shine light on the true mechanisms behind the disorder and allows you to broaden your conception of the disorder. Understanding that SUD is a chronic disease and comparing SUD to other chronic diseases provides some critical insights for researchers, other professionals, and the general public alike. While many people have a hard time accepting that SUD is a chronic disease, much like heart disease or cancer, it has an impact on the brain and body, not unlike other conditions.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defines a chronic condition as a long-lasting health condition that requires ongoing medical care, limits normal daily activities, or both. The term chronic is also broadly used to define conditions that last one year or more. Examples of other chronic diseases include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease.

When SUD is understood as a challenging and long-term illness, like other chronic illnesses, it makes way for a deeper understanding of the disease itself.

Similarities

SUD is a disorder of the brain, much like heart disease is a disorder of the heart. Just as heart disease disrupts activity in the heart, SUD disrupts activity in the brain. Like other chronic illnesses, SUD can be genetic, as well as environmental, and like other chronic disorders, it is oftentimes the outcome of high-risk factors that were made by personal choices, much like smoking is to lung cancer or poor diet is to obesity, also common chronic diseases. SUD is a health issue, not an indication of a moral flaw. The disease should be treated rather than the individual punished.

SUD is like many other chronic diseases in the following ways:

- SUD is preventable

- SUD is treatable but not curable

- SUD changes the responses formed by the brain

- Though it is not necessarily fatal, its effects can lead to death if left untreated

Addiction and the Brain’s Reward System

When discerning the relationship between the brain and addiction, it is important to understand that substance use has power over people’s lives because it tricks the brain. A major function of the brain is to facilitate the production and release of neurotransmitters or chemical messengers. One is dopamine, the pleasure chemical.

Any pleasurable experience can be attributed to dopamine. It motivates a person to pursue survival and continue doing the things necessary to sustain life, such as eating, drinking, and exercising. However, the brain also releases dopamine when exposed to substances like nicotine, alcohol, methamphetamine, or heroin. When long-term or substantial substance use occurs, the brain releases significantly higher levels of dopamine.

In fact, substance use can flood receptors with dopamine quickly, providing anywhere from two to ten times the amount of dopamine achieved with activities like eating and exercising. As this process re-occurs over time, the brain adjusts to the difference in dopamine levels, and the dopamine has less of an impact. As a result, the substance becomes less and less rewarding, increasing both cravings and the amount of substance needed to attain the same effect. This effect is called tolerance.

As individuals experience higher and higher tolerance levels, they must use more and more of the substance on a more frequent basis. Meanwhile, the brain has adjusted so it can function in the presence of the substance, leaving the individual feeling desperate to achieve the sense of normalcy they experience while using.

This is when an SUD develops—individuals begin using a substance not because they are getting high but because they are avoiding getting low. They are merely trying to feel normal and avoid withdrawal rather than trying to attain the pleasurable feelings they once experienced. Too often, this is why people continue substance use despite the health consequences and negative effects their actions have on their finances, career, and relationships with families and friends.

Frontal Cortex

In a healthy brain, impulse control is an important cognitive function, balanced with normal judgment and decision-making skills to promote rational behavior. In the brain of someone with SUD, the frontal cortex’s reduced function also reduces impulse control when it comes to substance use. This occurs even though the person may be aware of the consequences. For this reason, someone suffering from SUD may want to quit using the substance, but their compromised self-control and desire to obtain relief from withdrawal systems override reasoning and willpower.

Let’s look at a few ways we describe substance use disorder’s effect on the brain:

Substances Are Mind-Altering

The above circumstances are why many substances are described as “mind-altering.” These substances alter the person’s state of consciousness during use. They also alter the brain’s function indefinitely until the person stops using the substance for a prolonged time.

Another common way many people describe SUD is by stating that substance use hijacks the brain. When taken literally, this analogy explains exactly what prolonged use of a substance does to the brain. SUD can effectively take over multiple brain processes until it no longer functions as it used to before substance use. Eventually, the individual has diminished control over their own actions.

SUD and Brain Injury

It is interesting to compare symptoms of a brain injury to the frontal cortex with symptoms of SUD. Some of these include loss of coordination, loss of impulse control, difficulty following steps to complete a task, diminished insight in problem-solving, social behavior and personality changes, mood fluctuations, and lack of motivation. These are often symptoms of SUD as well, and it makes sense that the neuroimaging of the SUD brain shows thwarted activity in the frontal cortex.

SUD Treatment

SUD, like other chronic diseases, is treatable. There are many different types of treatment and programs available, and it is important to understand that not every person suffering from SUD will respond to the same approach. The most successful programs incorporate a holistic approach to treating SUD, combining exercise-based therapies like running with creative therapy, group therapy, and psychotherapeutic approaches like cognitive behavioral therapy. Many times, prescribed pharmaceutical medicine is also necessary to treat substance use disorders.

It is important to remember that many people with SUD also have a second diagnosis of mental illness, such as depression or anxiety. In these cases, it is important to treat both conditions because they both affect the brain as well as one another. Dual-diagnosis treatment has demonstrated a higher chance of positive outcomes than treating disorders separately.

Finding Recovery From SUD

The last component in understanding the relationship between the brain and addiction is the realization that individuals can recover, and so can the brain in many cases. Recovery is the goal as we treat every person with SUD. However, the goal is not just recovery from SUD, but recovery of the brain, as well.

While there is still much research that must be done to fully understand the brain’s ability to regain full function after extended SUD, researchers can use some of the same techniques mentioned above to compare brain activity. Neurological imaging of brains taken at different stages of recovery shows that recovery of brain function can be directly correlated to how long the person has abstained from substance use. The longer the brain is free from interference from substances, the more normal activity it shows.

One study shows that after 14 months of abstinence, a brain affected by methamphetamine exhibited a return of brain dopamine function to nearly normal. There also appears to be improved executive functioning and short-term memory, as well as larger cerebellar volumes in a brain affected by alcohol use disorder after only several days of abstinence from alcohol.

The Importance of Abstinence

Abstinence is vital to the recovery of the brain. Without it, the brain will continue to be tricked by substance use. While there is no cure for SUD, the best way to prevent relapse is to develop strategies to avoid triggers, navigate emotional situations, and respond without substance use.

While recovery is a lifelong task, it does get easier with time. One of the chief components of everyday, long-term recovery is a strong support community you can turn to for encouragement, support, strategies, and more. By building and maintaining a supportive community, you can significantly decrease your chances of relapse, boosting the likelihood that your brain will return to its full, functional capacity.

Preventing Substance Use Disorder

Like many other diseases, SUD is preventable. Educating people about the dangers of use and prolonged use of substances and the harmful effects they can have on the body decreases their chances of developing SUD. While the brain is functioning normally, it can make a conscious decision not to use mind-altering substances.

The Sober Curious Movement is a prevention-adjacent group that has successfully motivated many alcohol users to examine their relationship with alcohol. By considering the impact alcohol or another substance has had on your life, you may find value in moderating or even ceasing use altogether. The Sober Curious Movement aims to prevent some people with a dangerous relationship with alcohol from experiencing SUD.

Brain + Addiction = A Need for Proper Treatment

After gaining an understanding of how SUD affects the brain, it may be clear that you or a loved one needs treatment. If you are still unsure, take the “Do I Need Rehab?” quiz to get a better idea of who should seek professional help for SUD. Here you will also learn more about your treatment options and the potential for living a full and functional life in recovery from SUD. Healing is possible—reach out to us today to learn more about how you can get started.

Sources:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Preface: Drugs, brains, and behavior – The science of addiction. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/preface

- Medical News Today. (2017). What is addiction? Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318139

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). About chronic diseases. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm

- Harvard Medical School. (n.d.). Brain circuits involved in addiction identified. Retrieved from https://hms.harvard.edu/news/brain-circuits-addiction

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Drugs and the brain. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/drugs-brain

- Berridge, K. C., & Robinson, T. E. (2001). Parsing reward. Trends in Neurosciences, 24(11), 941-948. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01981-6 http://www.jneurosci.org/content/21/23/9414.full